The relationship between medicine and research is constant, feeding back and forth through collaborations, medical trials, and publications.

While it’s becoming more common for researchers to work collaboratively with clinicians, a clinician actively taking on research is still rare.

Dr Hugh Paterson is a retired cardiothoracic surgeon currently researching mitral valve replacement at the University of Sydney. “As a clinician, you know, I see problems and I want to try and make them better,” Hugh says, “I felt I had a responsibility to investigate and get involved in research. So, shortly after I became a consultant, I attached myself to another research team doing large animal studies, and that was great exposure. That was about 30 years ago.”

Fifteen years later, Hugh had set up his own mitral research program, collaborating with other researchers to assess and fine-tune mitral valve surgery. Hugh’s current research program involves a sheep model of mitral valve replacement.

Related: Dr Laurencie Brunel: Understanding the impact of mitral valve replacement

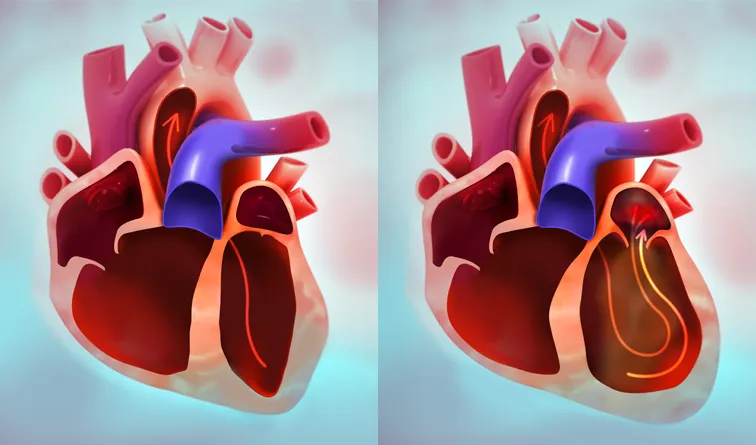

The mitral valve separates the left atrium from the left ventricle, opening to allow blood to flow from the atrium to the ventricle and closing as pressure builds in the opposite direction. Heart disease remodels the left ventricle, forcing the leaflets of the mitral valve to adapt, enlarging and moving more stiffly. That adaptation reduces the mitral valve’s ability to close completely, and blood leaks back from the ventricle into the atrium; this is known as ischemic mitral regurgitation (IMR). The worse the IMR is, the harder the heart has to work to pump enough blood around the body, eventually leading to heart failure. The typical surgical treatment for severe IMR is a valve repair or replacement.

LEFT: blood flow through a normal heart

RIGHT: blood flow through a heart with mitral regurgitation

“In IMR, if we replace the valve, most surgeons chop out the entire anterior leaflet,” Hugh says, “[doing] that impairs left ventricular function. They don't need to do that. We've got to find a way of retaining it, either by better repair techniques or by using a prosthesis that allows retention of the anterior leaflet.”

In an earlier experiment, Hugh and his team found that even the least destructive intervention, splitting the anterior leaflet, impaired left ventricular function. ‘Impaired function’ may not sound all that dramatic, especially after open-heart surgery, but it is the first step toward congestive heart failure.

“I just don't want people to make the same mistakes I made,” Hugh says, “I did things that were a little less than optimal because I didn't know. And there are still lots of people doing suboptimal therapy for ischemic mitral disease.”

“I think we can make the results of open heart surgery for small groups of people better. There's an issue with treating the mitral valve where we lose left ventricular function,” Hugh says, “[when that happens] the patients don't do so well, about 15% to 20% of them die. And we can cut that down a long way. We can definitely get that down below 5%.”

Measuring the impact of mitral valve replacement is much easier now than it was 30 years ago. “This sort of research was carried out initially in the mid-eighties,” Hugh says, “And in those days they had a state-of-the-art computer with a massive 64-megabyte hard drive, and reams of printed paper strewn all over the floor. We've come a long way since then, but those guys back then, they did amazing work, and I just think, how lucky am I?”

These days, Hugh and his team use gold-standard Millar catheters paired with PowerLab and LabChart to record and analyze PV Loops. It’s a much tidier system; there is no more paper on the floor, no more messy signals, just high-fidelity data and cutting-edge analysis in neatly packaged digital folders. It is much easier to demonstrate the reduction in left ventricular function than it once was, but for Hugh, it doesn’t matter until clinicians get on board.

“I'd like to think that we can change thinking amongst clinicians,” Hugh says, “They’ve got to understand that the mitral valve is actually very important to left ventricular function… if we can get the information that will one day change thinking, I’d be ecstatic.”

Find out more about Hugh’s research

Brunel, L., et al. “An Ovine Model of Mitral Bioprosthetic Valve Induced Left Ventricular Outflow Tract Obstruction Due to Systolic Anterior Motion of the Fully Retained Native Anterior Leaflet.” Heart Lung and Circulation, vol. 28, Jan. 2019, p. S74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hlc.2019.02.030

Brunel, L., et al. “Splitting the Anterior Mitral Leaflet Impairs Left Ventricular Function in an Ovine Model.” European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery, vol. 63, no. 1, Nov. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1093/ejcts/ezac539