Dr Emily Zimmerman

Developmental Speech Physiologist

The ability of the human body to grow and develop throughout life, to maintain homeostasis and to reproduce is both incredibly complex and beautifully precise. And nowhere is the precision of biology more obvious than in a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU).

Here, the lives of infants born before 37 weeks depend on advanced technology - incubators, respirators and feeding lines - alongside the cumulative knowledge and care of a team of nurses, pediatricians and developmental biologists. Thanks to the technology and specialized treatment, the prognosis for preterm infants is continually improving. Even in developing countries, advancing knowledge about interventions such as kangaroo care is saving lives. But the problem is a vast one, with more than 15 million preterm births worldwide in 2014, and as the focus moves from simple survival to long-term, healthy development, it is becoming more complex.

15 million

preterm births worldwide in 2014

Preterm birth complications are the leading cause of death among children under 5 years of age, responsible for nearly 1 million deaths in 2013.

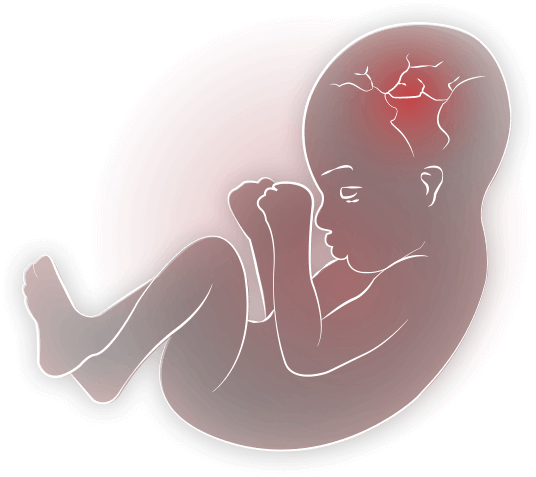

“When babies are born early, they are taken from a very rich and complex environment - the ideal recipe for development,”

explains Dr. Emily Zimmerman, Director of the Speech and Neurodevelopment Lab at Northeastern University in Boston. “In the womb everything is perfectly programmed to give the right stimuli in the right order to foster an infant’s emerging senses - first touch, then vestibular, olfactory, auditory and vision. Part of our research is looking at ways to mimic the womb environment with the purpose of helping these preterm infants get back on track with their development - even small environmental changes help, like touch, glide motion for vestibular stimulation and specific sounds to stimulate the auditory system. My long-term hypothesis is that if we can get these pathways integrated early for preterm infants then perhaps their speech, language, and cognitive development will also be intact, and their developmental trajectory will be improved.”

An infant's emerging senses

TOUCH

VESTIBULAR

OLFACTORY

AUDITORY

VISION

The number of measurable parameters can be limited for those studying the developmental physiology of fragile and infection-prone infants. In Emily’s lab, one of the key parameters is suck patterning, also known as non-nutritive suck, as it involves sucking without nutrients. It is an important indicator because it is centered in the brainstem.

“Suck assessment provides an early indication of the integrity of the central nervous system (CNS). This knowledge can be useful for both preterm and healthy infant populations to not only give us early insights into the CNS but also to predict subsequent neurodevelopment.”

While suck has long been a measure of infant health, it has only recently become a source of quantitative data. Emily worked with the Mechanical Engineering Department at Northeastern to design a suck device (though not the first) - a pressure transducer that attaches to a pacifier at one end and a PowerLab at the other, recording minute changes in patterns within each burst of sucking. “We look at suck amplitude, how many cycles occur within a burst, how many bursts occur within a minute, how many cycles occur within a minute, and how many cycles per burst. There are many fine spatio-temporal differences found in those measures that help us understand CNS activity.” Alongside these measures, she and her team simultaneously collect respiration, heart rate and calculate heart rate variability. “I wanted the flexibility in a data acquisition system to be able to add more sensors (respiration, ECG) depending on the project or the research questions. I’m not an engineer, but ADInstruments has allowed me to really tap into ease-of-use, connecting these sensors and different technologies into the system.”

“The additional cardiorespiratory signals are telling us how patterned the breathing and heart rates are and if perhaps suck pattern is coming at the expense of cardiorespiratory support or vice versa. And then, with the low frequency to high frequency heart rate variability, we are able to examine the inputs from the parasympathetic versus the sympathetic aspects of the autonomic nervous system and their role.”

At a micro level, Emily has recently started working with Dr. Jill Maron at Tufts Medical Center to find early, non-invasive biomarkers. “We are investigating expression levels of a speech and language gene to understand how it correlates with oral feeding ability and subsequently with speech and language development.

If we could determine at birth, by simply analyzing a drop of saliva, how an infant will both orally feed and perform in their speech and language development, we could develop timely and targeted interventions to improve both short and long-term outcomes.”

Preterm births in Puerto Rico

occur at a significantly higher rate

than that of continental USA

Emily is also looking at preterm birth on a macro level, joining a team of researchers who are investigating the role of environmental exposures in the high rate of preterm birth in Puerto Rico, which is significantly higher than that of continental USA - research under the leadership of Dr. Akram Alshawabkeh, Snell Professor of Engineering at Northeastern and Dr. José F. Cordero, the Patel Distinguished Professor in Public Health at the University of Georgia. Other members of this group have been looking at maternal health through pregnancy for a center grant called Puerto Rico Testsite for Exploring Contamination Threats or ‘PROTECT’ and now we are building on this with a newly funded Center for Research on Early Childhood Exposure and Development in Puerto Rico ‘CRECE’ to look at influences of a mixture of environmental exposures and modifying factors on fetal and early childhood health and development in an underserved, and highly-exposed population in Puerto Rico’s northern coast. “We’re so excited to look for these outcomes. We really hope that through this research we can influence maternal behaviours or even guide environmental regulations to result in healthy children who are free of delays.”

As a certified speech pathologist as well as a developmental speech physiologist, Emily has created a round of tests to look at feeding, speech, language and cognition to understand the development of infants that have been exposed in utero to these environmental factors - but it doesn’t stop there. “Our project has a community outreach and translation core, which serves as the public interface for CRECE and brings together residents, government agencies, researchers, and community organizations to improve communication and practice around children’s environmental health. The idea of translating these results back to the community is where my passion comes from - to understand some of the theoretical but also clinical questions that help those infants as well as the community.”

“We’re so excited to look for these outcomes. We really hope that through this research we can influence maternal behaviours or even guide environmental regulations to result in healthy children who are free of delays.”

La Perla, Old San Juan, Puerto Rico

Photo credit:

Steve Hardy

Her inspiration to be a scientist? She laughs. “I actually had no desire to be a researcher until pretty late in college. I’m a people person and I didn’t think that I could sit in a lab all day. That said, my niche within the field is perfect for me, because I’m interested in babies, and mothers, and nurses, and so I am able to fulfil the social aspect of myself. Then I’ve also developed a love of crunching data and working through statistics - that aspect is really compelling to me as well, data is so fun to play with! I would tell any student considering a career in science to go for it. I would say this is your path to anything you want to be. To know you are contributing to your field and helping real people is an amazing feeling.”

“To know you are contributing to your field and helping real people is an amazing feeling.”

Dr Emily Zimmerman

Developmental Speech Physiologist

Who is Dr Emily Zimmerman’s science hero?

“My PhD mentor, Dr Steven Barlow, is my science hero. I fell in love with anatomy and physiology through his undergraduate classes. In my later studies in speech-language pathology, Dr Barlow introduced me to the cohort of infants who are at-risk for feeding and developmental delays, and emphasized the need for quantitative physiological measures to make a real difference for this population. More than that, he is a really strong advocate for his students - he truly believed in me and my ability to contribute to this field. His ethics and scientific integrity will stay with me forever.”

Dr Emily Zimmerman with her science hero,

Dr Steven Barlow