Lessons from the Wild

How comparative physiology is redefining medical practice

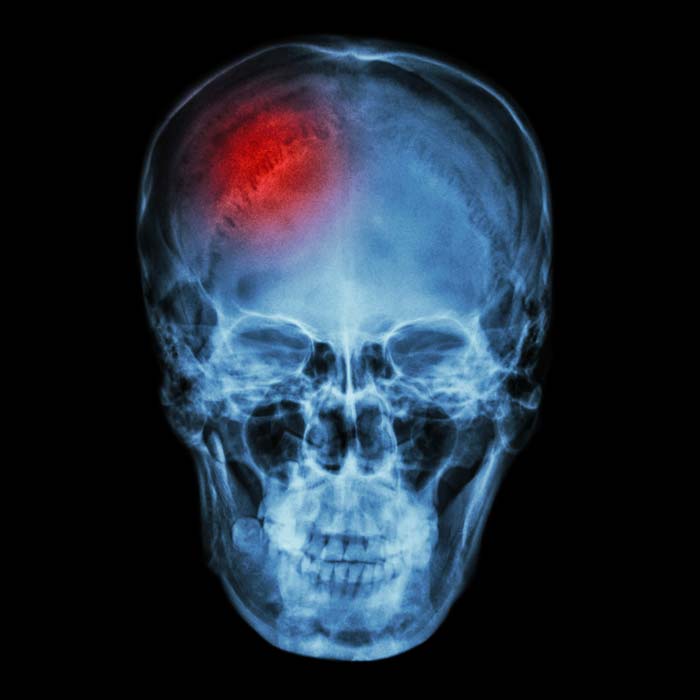

In a rock pool on the east coast of New Zealand, a small fish darts into a shadow. It’s a triple fin, a common kind of coastal fish, found all over the world. It’s brown and speckled, nothing out of the ordinary, and yet, as we talk on a beach south of Dunedin, Dr Tony Hickey assures us it could hold the key to understanding one of the world’s most prevalent and devastating medical conditions. A staggering 15 million people per year suffer a stroke. Worldwide, nearly 6 million die. According to the World Health Organisation, stroke claims more lives than AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis combined and many people are left with permanent effects on their ability to move and communicate. It’s hard to understand how a fish can help.

A stroke is caused by the interruption of the blood supply to the brain, depriving tissues of oxygen and nutrients, and causing damage to the brain. Tony explains that a similar lack of oxygen, or hypoxia, is something the triple fin experiences every day. “As it warms at low tide, the water holds less dissolved oxygen so a rock pool becomes hypoxic quite quickly in a way that mimics the lack of oxygen during a stroke. And yet this species of triple fin comes out with no damage - no muscle damage, no brain damage. From them, we may be able to work out how to protect the brain when strokes occur.”

Importantly, New Zealand also has more than the usual number of triple fin species, adapted to live in a broad range of coastal habitats. “If we have two fish that are very closely related, almost identical, and one lives in rock pools that can tolerate hypoxia and one in deeper ocean that can’t, then we have a really good chance of identifying the factors that allow the fish to protect itself from its environment.”

This inter-species approach has already yielded results for transplant surgery, thanks to the burrowing frog. In winter, the frog can freeze solid but it thaws out with no internal damage. How? Researchers found that as the temperature drops, the frogs hypersecrete glucose, perfusing their organs, increasing the molarity of their blood and preventing the formation of ice crystals - an amazing feat but also a potential method of prolonging the life of organs for transplant, allowing them to be transported further to where they are needed. Traditionally, organs from a donor could be safely kept for around six hours - when perfused with the synthetic glucose that researchers went on to develop, organs can be kept on ice for up to four days.

Each year 16,000 people require liver transplants in the

USA alone.

Tony is a researcher and lecturer in biochemistry and comparative physiology at Auckland University and he has an unique way of looking at life, a way of seeing connections between things that most of us would miss. Part of a research team that combines the skills of medical doctors, surgeons, biochemists and animal physiologists, Tony is not only advancing medical research, he is shining a new light on the value of biodiversity.

Even so, Tony says the practical reach of his research isn’t always obvious.

“A lot of the work we do can seem very esoteric or pure science-y, but that’s generally where the big changes in mindset often come from - there are major leaps that can come from studying animals that have solved problems. Instead of looking at a broken human system and trying to work backwards, we should look at systems that have already fixed the problem.”

Tony’s eye for links between animal environments and human medicine has grown out of an unusual mix of influences and a “little bit of luck.” He studied biochemistry and population genetics. He credits a research trip to Antarctica during his Master’ degree for kick-starting a fascination with animals’ ability to survive in extreme environments. Later, there was a stint at a diabetes research company, which fuelled yet another of Tony’s fascinations: mitochondria. With much of Tony’s work, mitochondria are now the focus, a link between all multicellular organisms and a constant source of insight into species adaptation and disease states in humans and animals.

"After visiting Antartica as a student, I became hooked on the diversity of life.”

When we meet he has just heard that a mitochondrial research publication of his has been nominated for top paper of 2014 in the American Journal of Physiology. Tony and one of his students used an ADInstruments Working Heart system to study how heart mitochondria produce ATP in real-time relative to the amount of oxygen they have.

“We wanted to see how the heart mitochondria behaved once that oxygen ran out. All of a sudden they began to consume ATP at a huge rate - we thought we’d actually made a mistake with our experiment - they consumed ATP at almost the same rate that they can make it.”

This gave them a really important insight into how diabetic hearts fail in heart attacks. “When we ran the same experiment with a diabetic heart we found they consumed ATP at the same rate as a healthy heart, but when they’re making ATP normally, they’re compromised.”

Tony’s enthusiasm for research seems endless – just like his list of current projects. He is working with the Health Research Council and Auckland Medical School’s Pancreatitis Research Group to better understand mitochondrial function in sepsis and pancreatitis. And with the Human Nutrition Unit to explore mitochondrial function and multiple organ failure in the face of obesity. He has recently made some major breakthroughs on heat stroke and heart failure. If this doesn’t sound like enough, he is also applying his research to measuring the impacts of climate change and ocean acidification. And he teaches.

We are really proud to support scientists like Tony, who apply such energy and passion into everything they do – and proud to feel involved in some truly amazing research.